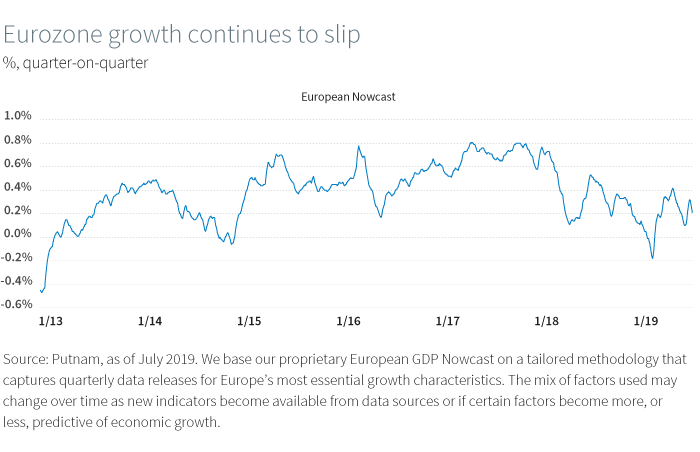

The central bank has set the stage for more monetary stimulus in a bid to improve the eurozone's cooling economy.

The European Central Bank (ECB) sent its strongest signal yet at the July meeting that monetary support for the euro-area economy will be stepped up. President Mario Draghi and fellow policy makers said they expect borrowing costs to stay at present levels "or lower" through at least the first half of 2020, opening room for a September reduction in the deposit rate from a record low. The ECB also signaled it may restart the bondbuying program. The central bank is clearly concerned about the drift in economic data.

The global downturn — a reflection of the trade war and China's slowing economy — is affecting Germany and the European supply chains that feed into Germany. In Germany, the eurozone's largest economy, manufacturing indicators look remarkably weak, and the labor market is beginning to feel the effects of the slump in manufacturing. In France, consumer spending has stagnated, raising the risk that domestic demand will start to weaken in the eurozone. Across the region, the gap between services and manufacturing is large, and there is the risk a further escalation in the trade war could be enough to tip the eurozone over. A hard Brexit could be the straw that breaks the camel's back. Still, we don't forecast a recession. Instead, we expect steady, sluggish growth.

Eyeing inflation and the Fed

Draghi, the outgoing ECB president, has said the outlook for eurozone growth was worsening and inflation remained well below the bank's target. The previous objective for inflation was "below, but close to, 2%." In July, the central bank talked about a symmetrical target in which inflation above or below the 2% target would be given equal weight. The ECB also indicated that the pass-through from a relatively tight labor market to inflation is operating more slowly and with a longer lag than they had expected.

The ECB is worried that a more dovish Fed will weaken the dollar and strengthen the euro.

In addition, the ECB is probably concerned about the Fed easing and the risk that the relative monetary stances of the two banks will shift. The Fed's rate move is expected to boost global demand and spill over to benefit the eurozone. The ECB is worried that a more dovish Fed will weaken the dollar and strengthen the euro. And the ECB's dovish tilt came hot on the heels of the Fed's. The big difference between the two banks is that the Fed has quite a bit of room to cut rates, and its balance sheet has fallen from its peak.

Limited policy options

What can the ECB do? The policy rates are already negative. Many analysts have expressed concern that, in a bank-dominated financial system, there is a negative interest rate at which the adverse effects on banks outweigh the benefits to the broader economy of lower rates. This is the "reversal rate." The ECB stopped expanding its balance sheet only a few months ago, and further expansion would quickly run into the constraints imposed by the capital key and by the bank's unwillingness to own more than 50% of a country's debt. And negative policy rates in the eurozone, a large capital exporter, are keeping global rates low.

The various constraints are not binding on the ECB because they are self-imposed and not bound by law. There are several options available. The central bank could cut interest rates and introduce some kind of deposit-rate tiering to reduce the cost to banks with large deposits at the ECB, thereby pushing the reversal rate down. The ECB could also suspend the capital key, and it could recuse itself from voting on bond restructuring to free up some space for more quantitative easing. All these measures would help. There is a clear benefit when a central bank signals that it is prepared to take new measures. But there seems little doubt that diminishing marginal returns are setting in for the ECB.

Using fiscal policy to boost the economy

Draghi said at the July press conference that the ECB cannot solve all of the eurozone's problems. Growth is slow in the region, and some of the factors contributing to the slowdown are hard to address. But the labor markets can be reformed, particularly in Italy. Draghi also said there are countries in the region that have the scope to provide fiscal stimulus. He meant Germany.

In Europe, fiscal issues are particularly sensitive, and Brussels has tried to interpret its rules with some flexibility. Fiscal policy is a tool for macroeconomic management, especially when monetary policy loses effectiveness. It is interesting to see that it is now being talked about more openly in many countries.

Next: Game of currencies

More from Macro Report

Download the Macro Report (PDF)Global growth is cooling as the trade war continues to erode business investment, manufacturing activity, and investor confidence.