Many governments around the world are mulling, or have provided, extra fiscal stimulus to boost their economies as the limits of monetary policy become more evident.

Fiscal policy is coming back to policymakers' agendas. There are many reasons for this, including worries about the inability of central banks to raise inflation despite low and, in many cases, negative interest rates; the need for infrastructure investment; the pressures politicians are under to “do something” in an increasingly fractured global political landscape; and the growing influence of modern monetary theory.

There are countries where some fiscal relaxation will take place in 2020.

There are countries where some fiscal relaxation will take place in 2020. New Zealand is about to deploy some fiscal stimulus. In Japan, a supplementary budget for this fiscal year and the initial budget for next fiscal year will provide stimulus that may boost GDP by as much as 0.5% over the next 18 months or so. That along with spending for the summer Olympic Games in Tokyo will improve Japan's outlook in 2020. Headline GDP growth is likely to be stronger by the second quarter of next year. However, we doubt this round of fiscal spending will be any more successful in lifting Japan's medium-term growth prospects than the previous round. It is also hard to see inflation getting anywhere close to the Bank of Japan's 2% target.

Cloudy outlook for the United Kingdom

In the United Kingdom, some fiscal relaxation is certain after the December election. The major parties had engaged in competitive bidding for the attention of the electorate. The Tory Party was actually forced to backtrack on one of its promises when independent analysts pointed out how ludicrous it was. Electioneering aside, there is a widespread recognition now that the austerity policies of David Cameron and George Osborne were inappropriately restrictive.

We can't be sure how much overall relaxation there will be, and what the balance will be between tax changes and higher spending. Still, there will be some fiscal shift, and it may well be quite large. What impact this will have on the economy is less clear. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson won a decisive majority in the December 12 general election, paving the way for the U.K. parliament to trigger a long-delayed split with the European Union. The Conservative majority is likely to approve the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement.

Some analysts argue that the removal of Brexit uncertainty and a fiscal boost will provide strong economic results in 2020. We are less convinced, partly because the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement says nothing concrete about future trade relations. They are still to be negotiated, and the claims made by Boris Johnson that a comprehensive and favorable agreement on future relations can be agreed quickly are an empty fantasy. We see little prospect of a sustained recovery in corporate investment until this uncertainty is resolved. Future U.K. and EU relations could support British economic activity, but it's going to take a while before the new government sets out clearly what it wants to negotiate. The economy may well do better in 2020, but not by much. The long-term outlook for Britain will remain cloudy until these uncertainties are resolved.

Fiscal headwinds in the United States

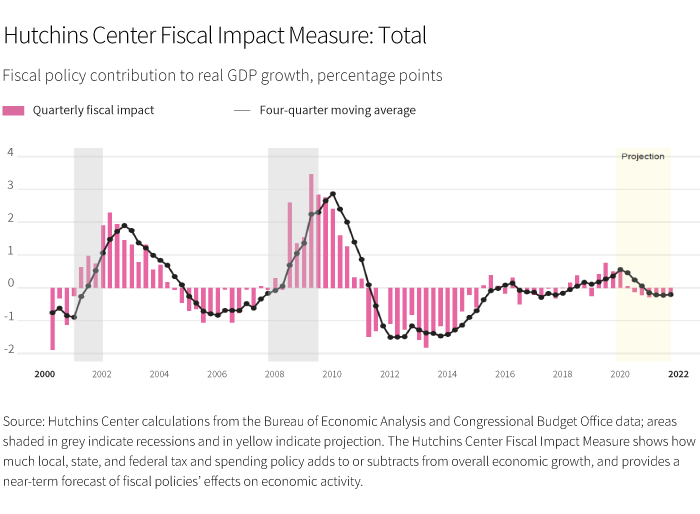

It is worth noting that the United States had its burst of fiscal activism with the corporate tax cuts passed at the end of 2017. The IMF estimates the fiscal deficit, in cyclically adjusted terms, is now at 6.3% of GDP. This fiscal expansionism brought a spurt of growth. However, it has done virtually nothing for long-term growth prospects because corporate investment was undercut by the trade war, and companies spent their tax gains on stock buybacks.

So, investments remain weak. The boost the economy got from the increase in the deficit is now ending. According to the Hutchins Center's measure (see chart above), the U.S. economy is about to see a fiscal tailwind become a headwind.

The limits of monetary policy

This year has been one of substantial monetary easing. Most importantly, the Fed cut interest rates three times and engaged in aggressive efforts to control the front end of the yield curve. The ECB cut its deposit rate into negative territory and restarted its quantitative easing (QE). India, Brazil, China, and a whole raft of emerging-market central banks have also lowered rates. It was a big year for doves.

The Fed is determinedly on hold in lowering rates further. Of course, if we tumble into a recession, central banks will become much more aggressive, but the conversation about monetary policy is rather different now after this year's moves. Either way, it's hard to imagine that 2020 can see a repeat of 2019's large-scale easing.

Next: Charting the link between rates and markets

More from Macro Report

Download the Macro Report (PDF)2020 is likely to be another year of sluggish growth with continued risk of a sharper downturn.