- Inflation risk is the risk that the purchasing power of a retiree’s savings erodes due to rising prices.

- Addressing inflation risk by allocating to asset classes such as commodities, treasury inflation-protected securities (TIPS), and/or real estate investment trusts (REITS) is often inefficient.

- We believe the best hedge for inflation is a fully invested portfolio combined with active management across the glide path.

A long-term portfolio needs a strategy to deal with inflation risk, which threatens to erode purchasing power. All investors will grapple with this risk, although it is most severe for those fast approaching retirement or already retired.

Prudent target-date managers should understand the effects of inflation risk and the best ways to manage it within the structure of a glide path. Attempting to hedge it is fraught with challenges and inefficiencies.

Considerations when seeking to mitigate inflation risk

Despite the challenge of hedging inflation risk, future and current retirees need not feel discouraged. One key reason is that Social Security Administration (SSA) benefits are, for the most part, insulated from inflation risk. That’s because SSA benefits receive a cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) related to increases in the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W).1 Putnam research finds that an individual with a lifetime income stream similar to that of the median household could expect SSA benefits to contribute 35% of their ending salary.2 Assuming a 75% income replacement rate, that means that the median participant could expect ~47% (35 ÷ 75) of his/her retirement income to adjust with inflation automatically.

Incorporating alternative asset classes

Many target-date managers attempt to hedge inflation with an allocation to assets that are expected to perform well in an inflationary environment. The typical assets cited are commodities, TIPS, and REITs. Unfortunately, all of these assets come with additional risks that might make them a poor fit for a static allocation.

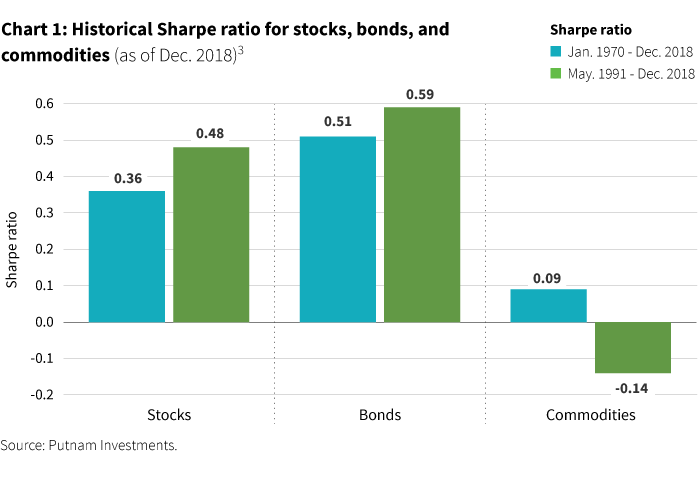

Commodities, for example, as represented by the S&P GSCI Index, have delivered less than half of the Sharpe ratio of stocks and bonds since the index inception in 1970. Even worse, the index has realized a negative excess return since it went live in 1991 (see Chart 1). Consequently, while inflation has eroded the purchasing power of a dollar over that time, commodities exposure has done little to hedge that risk.

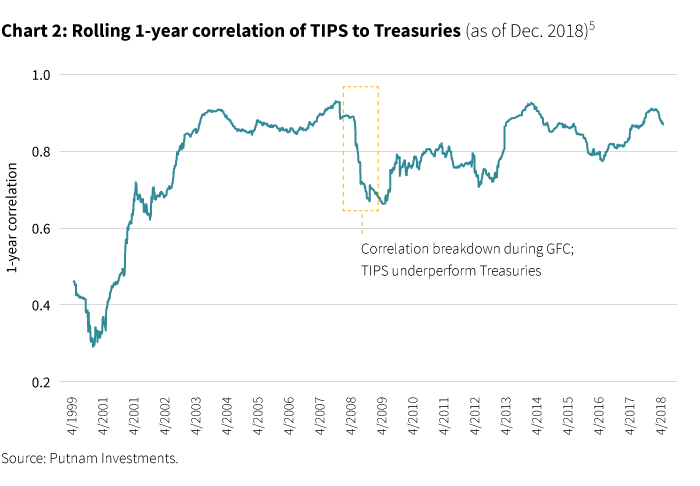

TIPS, which benefit from principal adjustments tied to CPI, might seem like a better hedge, but they can still suffer in a rising-rate environment. For example, if break-even inflation is static but real yields increase, TIPS will likely suffer. In fact, interest-rate risk has dominated TIPS since they were first issued by the U.S. Treasury in 1997. Additionally, there is evidence to suggest an imbedded liquidity premium in TIPS.4 During part of the 2008 Financial Crisis, as nominal yields continued to fall, real yields experienced a sharp spike, causing a divergence in the performance between TIPS and Treasuries. Chart 2, which plots the rolling one-year correlation, shows the break in this relationship at that time, but otherwise confirms the high correlation between the two asset classes. Given this correlation to Treasuries, it is not clear that TIPS warrant a strategic allocation in a glide path portfolio.

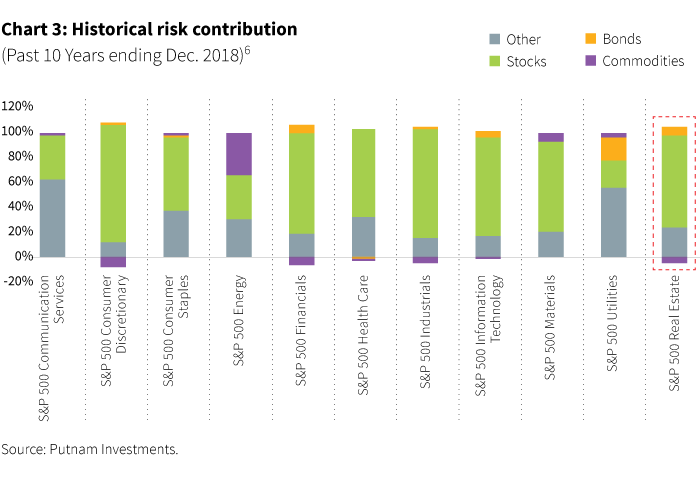

Finally, REITS are another potential hedge, but they are dominated by equity risk with some additional sensitivity to interest-rate risk. For that reason, it is hard to argue that they deserve a strategic allocation in a retirement portfolio more so than any other equity sector (see Chart 3). In fact, one could argue that energy sector stocks (since they are correlated to commodities) or health-care sector stocks (since they are a better fit for retiree spending) would be a better static inflation hedge. Nevertheless, we hesitate to recommend static, permanent sector allocations, as they are difficult to justify from a quantitative perspective. We believe that sector tilts are better left to a dynamic allocation process around an unbiased benchmark.

A more efficient way to protect against inflation

Another way a target-date fund manager can account for inflation is by considering real returns, which look at return in excess of inflation for asset class assumptions used in designing the glide path allocations. It is also important to emphasize that stocks have historically generated a positive real return of around 6%.7 Though not an explicit hedge, for investors concerned about the erosion of purchasing power, owning stocks has more than made up for the effects of inflation (equity prices reflect discounted earnings, which are priced in nominal terms).

Plan participants should want a portfolio that will protect them from inflation risk, but they should not suffer the lower risk-adjusted returns or hidden risks that often come with common strategies for hedging inflation. In our view, the best hedge for inflation is a fully invested portfolio. Additionally, this is a strong argument in favor of active management. It allows for dynamic asset allocation that invests in these asset classes only when inflation will pose a significant threat to the portfolio, and therefore, should provide better risk-adjusted returns.

Learn more about glide path design and dynamic allocation strategy: Listen to our webcast (February 27, 2019) and download our white paper, The glide path less traveled.

Notes

1 Another aspect of inflation risk to consider is that the consumption basket for a retiree might differ from that of the CPI calculation by, for example, including a higher exposure to health-care inflation. While this exposure is difficult to hedge directly, Health Savings Accounts (HSAs) provide at least some relief for individuals in qualified high-deductible plans facing high health-care costs. These accounts allow for greater tax advantages than retirement accounts on savings for qualified health-care expenses. Given the preferential treatment of these accounts, most advisors suggest that workers first maximize their employer match in retirement accounts, and then direct contributions to their HSA before making additional contributions to their retirement accounts.

2 Goldstein, B., “The glide path less traveled,” Putnam Investments. March 2018.

3 Stocks = S&P 500 TR Index (backfilled with IA SBBI S&P 500 TR USD prior to 2/29/1988), Bonds = Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Treasury 7–10 Year TR Index (backfilled with fitted blend of IA SBBI IT Govt. TR USD and IA SBBI LT Govt. TR USD prior to 2/29/92), Commodities = S&P GSCI TR, and Cash = Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Treasury Bills 1–3 Month TR Index (backfilled with IA SBBI U.S. 30-Day T-Bill TR USD prior to 2/29/92). All data is updated through 12/31/18.

4 Ajello, A., Benzoni, L., Chyruk, O., “Core and ‘Crust’: Consumer Prices and the Term Structure of Interest Rates,” The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. November 2014.

5 TIPS = Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Treasury Inflation Protected Securities TR Index, Treasuries = Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Treasury 7–10 Year TR Index.

6 Historical risk contribution is estimated using the output from a rolling 36-month multivariate regression for each S&P sector versus stocks, bonds, and commodities (S&P 500 TR, Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Treasury 7–10 Year TR, S&P GSCI TR). “Other” represents the portfolio of the realized risk not attributable to the three assets in the regression.

7 Using assumptions and methodology outlined in Goldstein (2018).

315927

For informational purposes only. Not an investment recommendation.

This material is provided for limited purposes. It is not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any financial instrument, or any Putnam product or strategy. References to specific asset classes and financial markets are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations or investment advice. The opinions expressed in this article represent the current, good-faith views of the author(s) at the time of publication. The views are provided for informational purposes only and are subject to change. This material does not take into account any investor’s particular investment objectives, strategies, tax status, or investment horizon. Investors should consult a financial advisor for advice suited to their individual financial needs. Putnam Investments cannot guarantee the accuracy or completeness of any statements or data contained in the article. Predictions, opinions, and other information contained in this article are subject to change. Any forward-looking statements speak only as of the date they are made, and Putnam assumes no duty to update them. Forward-looking statements are subject to numerous assumptions, risks, and uncertainties. Actual results could differ materially from those anticipated. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. As with any investment, there is a potential for profit as well as the possibility of loss.

Diversification does not guarantee a profit or ensure against loss. It is possible to lose money in a diversified portfolio.

Consider these risks before investing: International investing involves certain risks, such as currency fluctuations, economic instability, and political developments. Investments in small and/or midsize companies increase the risk of greater price fluctuations. Bond investments are subject to interest-rate risk, which means the prices of the fund’s bond investments are likely to fall if interest rates rise. Bond investments also are subject to credit risk, which is the risk that the issuer of the bond may default on payment of interest or principal. Interest-rate risk is generally greater for longer-term bonds, and credit risk is generally greater for below-investment-grade bonds, which may be considered speculative. Unlike bonds, funds that invest in bonds have ongoing fees and expenses. Lower-rated bonds may offer higher yields in return for more risk. Funds that invest in government securities are not guaranteed. Mortgage-backed securities are subject to prepayment risk. Commodities involve the risks of changes in market, political, regulatory, and natural conditions. You can lose money by investing in a mutual fund.

Putnam Retail Management.